Virus variants and strains

先达基因 / 2022-01-17

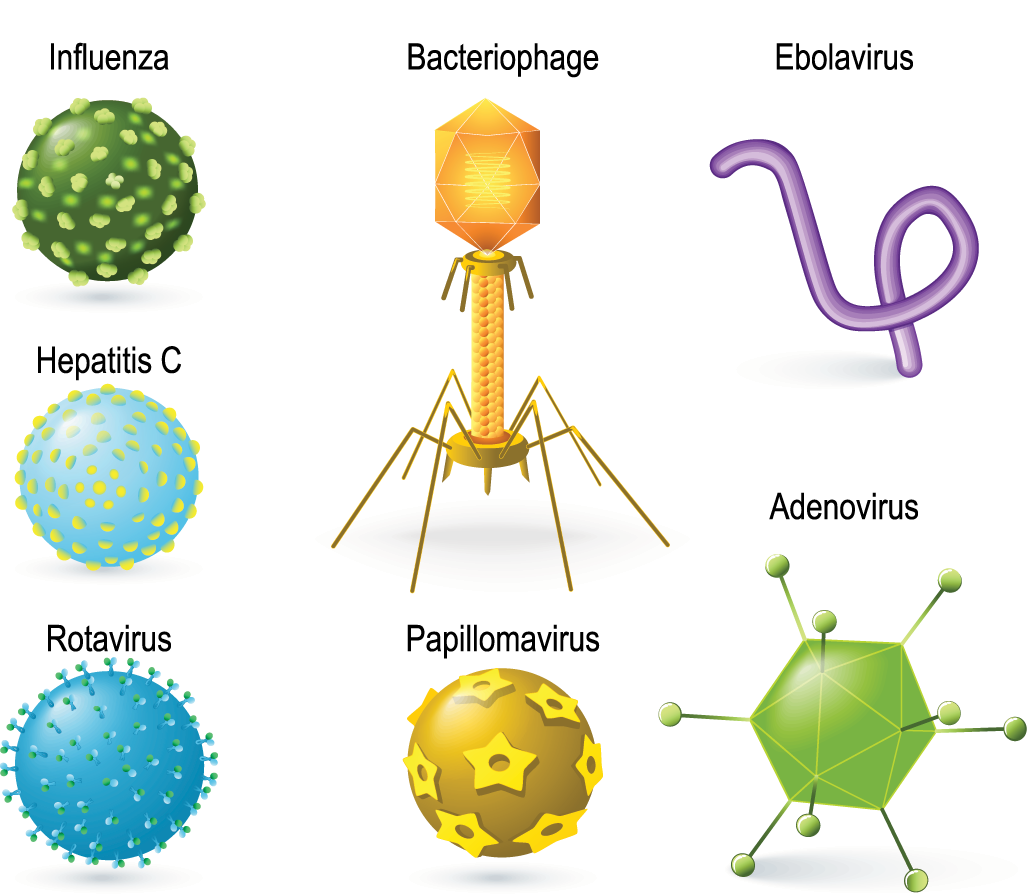

Some virus experts might not consider viruses to be alive. Yet viruses can reproduce. To do so, they hijack the cells of a host. They borrow the “machinery” in the host’s cells to copy the virus’ genetic code. Those host cells may spit out hundreds or thousands — even millions — of copies of the original virus. These new viruses then go on to infect more cells. Maybe the host will also sneeze out the viruses or otherwise release some to infect other potential hosts. And those hosts might be anything from people or plants to bacteria.

But each time a virus is copied, there’s some risk the host’s cell will make one or more errors in the genetic code of that virus. These are known as mutations. Each new one alters the genetic blueprint of the virus a bit. Mutant viruses are known as variants of the original.

Many mutations won’t affect how a virus works. Some might be bad for the virus. Others might improve how well the virus can infect a cell, or help the virus evade its host’s immune system. A mutation might even allow the virus to resist the effects of some therapy. Scientists refer to such new-and-improved variants as strains.

Keep in mind that all strains of a virus are variants. Not all variants, however, are different enough to qualify as a new strain.

And although coronavirus variants made news throughout much of the COVID-19 pandemic, any virus runs the risk of spawning new variants through mutation.

Indeed, mutations are one basis of evolution. Mutations that don’t benefit an organism (or virus), often die out. But those that make an organism more fit — better adapted to its environment — tend to become more dominant.